Feedback is a Two-Sided Coin

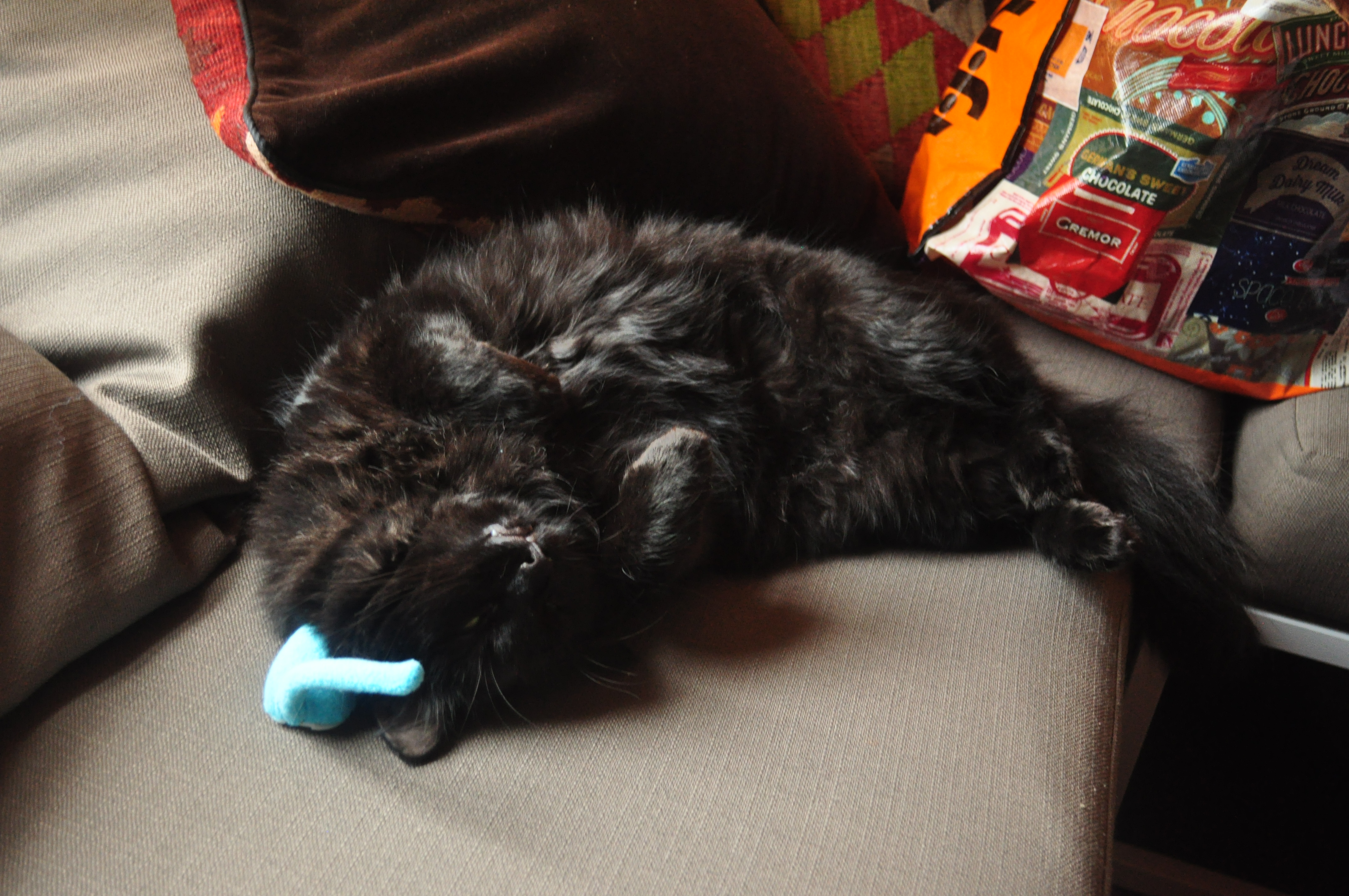

Every writer needs feedback, and I am not exception. I hunt for it more than my cat hunts for bugs. However, I was recently reminded that I really need to be careful with how I use and respond to it in the same way that Goose needs to realize its okay to hunt flies, but not bees. If I’m not careful about what feedback I take, I might just get stung.

Feedback comes from people. People are all unique and different from each other. They have different preferences. One person may hate a story another loves so every writer needs to be careful with how he or she uses feedback. Three personal rejections I received for the same story illustrate this fairly well.

Rejection A: “Thank you for giving me a chance to read “Berserker.” The opening scene of this grabbed me and it held my attention to the end, and I think it’s an interesting premise, but overall the story doesn’t quite work for me. In part, the changes of becoming a mother don’t feel like they’re really followed through on. In part, Mina’s change of heart at the end feels too abrupt to me, and the story doesn’t deal with the consequences of her getting caught committing an assault. I’m going to pass on this one for ____, but I wish you best of luck finding the right market for it. I appreciate your interest in ____and hope that you’ll keep us in mind in the future.”

After rejection A, I did make some changes. The feedback was specific,and in some ways, objective. It wasn’t just about what the reader likes, but pointing out a loose thread of plot. Once I was confident that I had tied up those loose ends, I started submitting it again. I got some form rejections, but I also received two more personal ones.

Rejection B: “I like the overall concept. The present tense isn’t helping you. The piece needs proofreading. I wasn’t as engaged as I’d have liked, and her victory over the curse was too easy. The piece relies on the curse selecting people who are definitely bad, which removes some of the most interesting moral potential from the story.”

I thought about making some changes after reading this, but in the end, all I did was fix a few typing errors. The story was about more than just Mina’s victory over the curse, and changing the nature of her victims would take the story somewhere I didn’t want it to go. I was nervous, but I kept submitting.

This was my next rejection:

Rejection C: “We thoroughly enjoyed your story–it’s one of my favorites so far. However, with limited space in the anthology, we didn’t feel like it was the best fit for our theme. It’s a unique premise and the writing is strong, so I have no doubt you’ll be able to find a home for Berserker. Thank you for sharing, and best of luck in seeking publication.”t

Yes, it is a rejection, but it does validate my opinions of my story. I knew when I sent it to this place that the piece was only loosely connected to their theme. In fact, it took me a fews days to convince myself it had any connection to the theme at all. Even though it got rejected, I’m glad I sent it. The piece is in progress with a few magazines and contest that are not restricted by theme, and to one more themed anthology that it is more directly related to. If at least one of those editors reacts like C, then hopefully, I will get an acceptance letter. If not, I’ll keep on sending it out.

I seek feedback wherever I can get it without spending more than a few dollars, but I am very selective about how I use that feedback. We should all analyze and think critically about how we use the feedback we get. Here are a few tips for doing this:

- Reflect on your initial reaction to the feedback. If it is something like “Oh, that makes so much sense! I can’t believe I didn’t think of it myself,” then you might just want to take their advice. If it makes you cringe, ask yourself why.

- Does the reader seem to get the point of the piece? If your answer is yes, then you might use their suggestions. If the answer is no, then you probably shouldn’t take their advice. However, if they didn’t get it, then there must be a reason. Try and figure out what it is so the next reader does “get” your piece.

- What effect will the suggested revisions have on your piece? Don’t be afraid to explore and take risks, but in the end, you probably should take advice that feels wrong. If it brings your story in a direction you know you don’t want it to go, then don’t do it.

- Think about how the feedback is framed. Is it about the editors preferences? or an objective comment about the structure, plot or character? Are they using words such as like, prefer or want? These might signify the response is based on their personal preferences. If they use more specific, concrete language, you can get a better idea of whether or not its a piece of advice you want to take.

Remember, the story is your creation. Feedback can help you see things you got too close to notice. It can help you help other people to appreciate your work. However, if you let it control your work, and you find yourself writing to please one editor or another, then your writing will no longer be your own, and more than likely, it will get worse, not better.

Hunt for feedback like an alley cat stalking a mouse. Use it as selectively as a spoiled house cat who only likes a few flavors of fancy feast.